One of my favourite non-fiction books is The Running Hare by John Lewis-Stempel. Lewis-Stempel is a hill farmer who rents a field to see if it is possible to recreate the wildlife-rich arable land that was once so common across Britain, before modern farming practices contributed to biodiversity loss. Over the course of the book, he charts how he works on the field using traditional ploughing techniques, scattering wildflower seed at the boundaries, not using pesticides, weed killers or fertilisers and gradually sees wildlife return. It is an incredibly uplifting story that shows how much can be done to bring wildlife back (and the integral role that farmers can play in this, if only they had the right support from government - but lets not get political!)

One of my favourite passages is John’s description of meeting a hare on the road near his newly-acquired field, which he has just discovered to be sterile and wildlife-free.

“...a jack hare runs, with the rocking-chair gait peculiar to the species, down the lane towards me.

He stops, and glares with golden eyes. Hares have the chiselled head of horses, the legs of lurchers - and the eyes of lions; the ancient Chinese considered the animal so other-worldly they decided its ancestor lived in the moon.

The hare, now up on his hind legs, cock-eared, continues to look at me, unblinking."

If you’ve ever seen a hare, then you’ll be familiar with this experience. I’m lucky enough to live in North Northumberland, where we still have enough space and biodiversity for animals like the brown hare to exist in relatively high numbers and so we see them fairly regularly, at least from a distance and usually in the middle of a field although one also likes to lurk around the local Haven caravan park!

But I still remember the first time I came face-to-face with a hare on a walk; that moment of surprise as we stood looking at each other, before he darted away with the ‘rocking-chair gait’ as Lewis-Stempel so aptly describes it.

Lewis-Stempel goes on to describe the Middle English poem ‘The Names of the Hare’, which lists 72 synonyms for the animal, including ‘the starer', 'the skidaddler', 'the wild one' and my favourite 'the race-the-wind', reflecting the fact that a hare being pursued by a predator can reach speeds of up to 45mph!

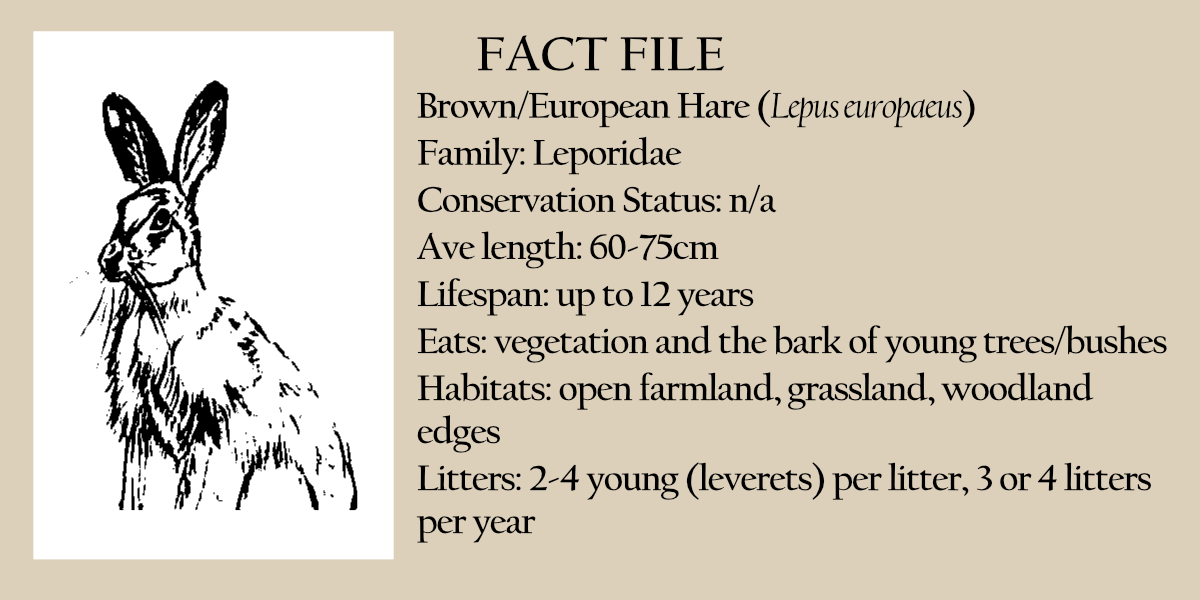

‘Drawn to…’ is a series of short articles diving into the lives of the wildlife of the British Isles. From appearance and habits to their role in culture and folklore, these articles will always include some fascinating facts as well as some of my favourite sketches and illustrations!

You can probably tell that I find hares fascinating and that’s because although I do get to see them now and again, they are still a creature of mystery and wonder to me.

Hares have been a symbol of fertility and reproduction since the Ancient Greeks, who associated the animal with Dionysus (god of wine and fertility), Aphrodite (goddess of love and procreation) and Artemis (goddess of the hunt, wilderness, wild animals and the moon). The Christian church had mixed feelings about the hare. Medieval representations are sometimes positive: because of the hare's habit of hiding from predators in crevices, they were taken as representing Christians or the Church in times of persecution (hiding in the rock of Christ). However, hares were also assumed to be hermaphrodite, and thus 'inconstant, neither man nor woman, neither faithful nor treacherous, unstable' and they came to be connected with ideas of lust and homosexuality.

We’ve had brown hares in Britain since as early as 500-300BCE and so although not a ‘native’ the brown hare is considered a naturalised species, with a population that spans England, Scotland and Wales (there is a presence in Northern Ireland, but it isn’t widespread there). FYI - the only native British hare is the mountain hare, which can still be found in higher latitudes in Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Hares tend to be golden brown in colour with a pale belly and a white tail and are noticeably larger than a rabbit, with longer legs and ears that end with a distinctive black tip. Hares do not burrow, but create a shallow scrape or 'form' in soil or grass where they rest. The young are born fully-furred with eyes open so that they can be left for long stretches in the form whilst the mother forages for food. Males are called ‘Jacks’, females are ‘Jills’ and the young are ‘Leverets’; a group of hares might be refered to as a 'down', a 'husk' or a 'leash'.

Generally nocturnal and shy in nature, their behaviour changes in spring, when they can be seen chasing one another around fields in daylight. They are particularly famous for ‘boxing’ or fights between two hares where they rise to their hind legs and pummel each other with their front legs in the stance of a boxer. Whilst it used to be thought that boxing hares were males fighting over females or territory, it is now understood that many of these fights are simply females warning off an amorous male (or testing his stamina!)

The hare in literature

It is this sort of performative and time-specific behaviour that has made the hare famous, with the English idiom ‘mad as a March hare’ coming in to use as early as the sixteenth century. The idea of ‘mad’ behaviour in the breed was then cemented by Lewis Caroll in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland at the tea-party which Alice attends with the March Hare and the Mad Hatter.

By contrast, John Clare, the early nineteenth century English poet and son of a farm labourer, described these spring-time hi-jinks more gently in his 'Hares at Play' (written sometime between 1812 and 1831):

The birds are gone to bed, the cows are still,

And sheep lie panting on each old mole-hill;

And underneath the willow's gray-green bough,

Like toil a-resting, lies the fallow plough.

The timid hares throw daylight fears away

On the lane's road to dust and dance and play,

Then dabble in the grain by naught deterred

To lick the dew-fall from the barley's beard;

Then out they sturt again and round the hill

Like happy thoughts dance, squat, and loiter still,

Till milking maidens in the early morn

Jingle their yokes and sturt them in the corn;

Through well-known beaten paths each nimbling hare

Sturts quick as fear, and seeks its hidden lair.

The modern plight of the brown hare

I don’t know when I’ll stop being shocked that species that we know are in decline can still be legally hunted or killed. Although a species of conservation concern, brown hares have minimal legal protection because they’re considered a game species - but unlike other game, hares can be shot throughout the year, including through their breeding season - making them doubly unlucky.

Add to that, after being hunted for centuries in the UK from beagling (hunting with packs of beagles) to coursing (an aristocratic pursuit, involving greyhounds), and modern ‘lamping’ (where groups go out at night with bright lights to spook hares in the field so that they can be killed) our general lack of care for the environment coupled with modern industrial agriculture is also putting pressure on hare populations. Hares don’t hibernate or store much body fat, so they need a constant, year-round supply of food, which they used to be able to find in places like hay meadows (except that Britain has lost 95% of its traditional hay meadows since the end of the Second World War) and field-margins or hedgerows (150,000 miles of ancient and mature hedgerow have been destroyed in the past 50 years).

Without these landscapes that were rich in biodiversity and food for foraging hares, populations have been in steady decline since the 1960s, with some parts of Britain now in pockets of ‘local extinction’. In the mid 1990s, concern at the brown hare’s decline led to a government Biodiversity Action Plan, which had among its aims a doubling of the brown hare population by the year 2010. You’ll likely be unsurprised to hear that research at the University of Bristol found that this target was missed by a wide margin and that in addition to more action for habitat management and re-creation, measures need to be taken to reduce hare mortality (for example, by making hunting hares illegal).

If you’d like to do your bit to support the Brown Hare, you can find out more about ways to help on the Hare Preservation Trust website.

So sad! Very interesting though, and great pictures, thankyou

Beautiful art and writing. Thank you for sharing :)